A cross-border project in Asia unravels how a coveted but banned luxury product sourced from the protected Tibetan Antelope isn’t just thriving in the black market, but finding newer avenues to find buyers.

***

In the bustling streets of Srinagar’s Old City, in India’s Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir, the mention of “shahtoosh” elicits a violent shake of the head. There’s no shahtoosh here, we’re told consistently. It doesn’t exist anymore.

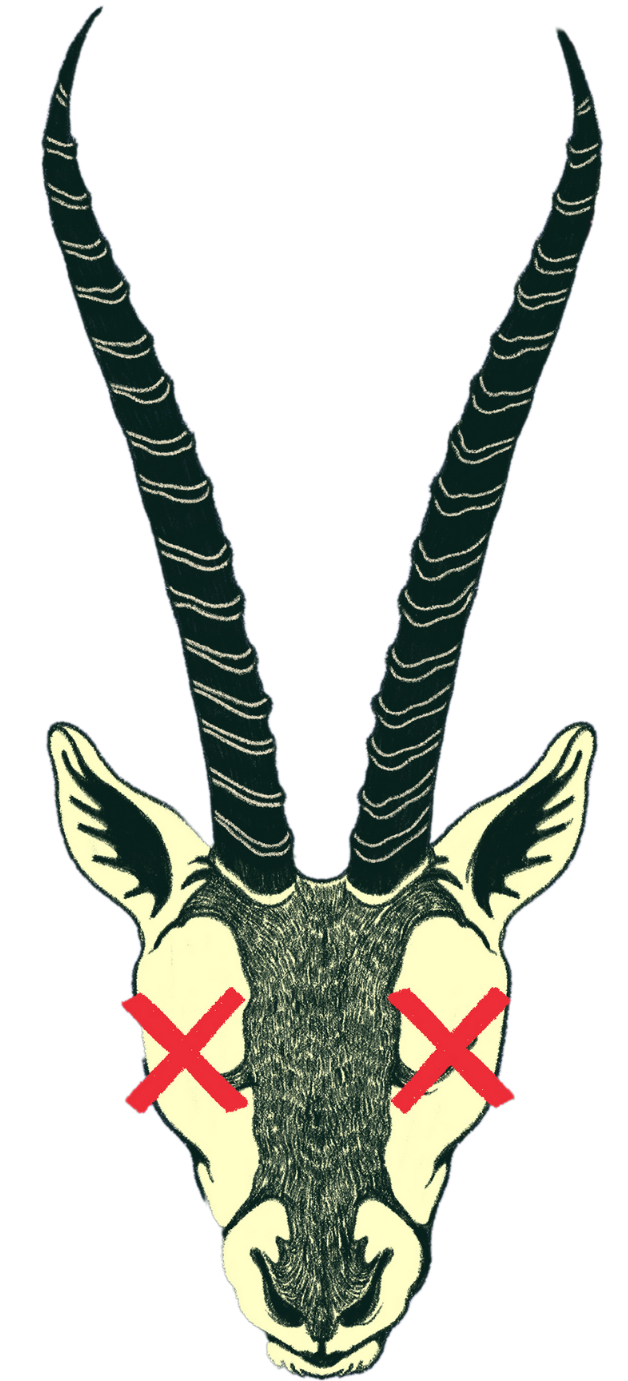

This denial is as present as the dark clouds of ongoing unrest in the region are pervasive. This is also in line with the global ban on shahtoosh trade since 1979 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). India banned it in 1979, and Jammu and Kashmir implemented it in 2000. The ban followed international scientific studies and revelations about the mass killings of a Himalayan goat species, the Tibetan Antelope or chiru.

The chiru is a Schedule-I species as per the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972 of India. According to the Wildlife Protection Society of India, it takes the life of three Tibetan Antelopes to make one 2m x 1m lady's shawl, and the life of five to six of them to produce a man’s shawl. The Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, is essentially to afford the animal the highest degree of protection. Yet, research indicates a high degree of precarity for the chiru. In a crackdown called ‘Operation Soft Gold’, India’s Wildlife Crime Control Bureau analysed shahtoosh seizures and cases between 2009 and 2020 in the country. Their report, published in 2022, found that the trade of shahtoosh has been “actively operational undercover in India in order to cater to the worldwide demand.”

A rare fabric coveted by the world’s high-society and political elite, shahtoosh trade is counted among the world’s most alarming wildlife crimes which continues to have an exclusive market, according to the 2024 World Wildlife Crime Report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The CITES Illegal Trade Database, documented 245 Tibetan antelope specimen seizures between 2016 and 2021 in India, Nepal, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the UK and the US.

with a scarf that may have been a gift from

Emperor Akbar, who loved shahtoosh.

Image: The Cleveland Museum

of Art via Google Arts & Culture

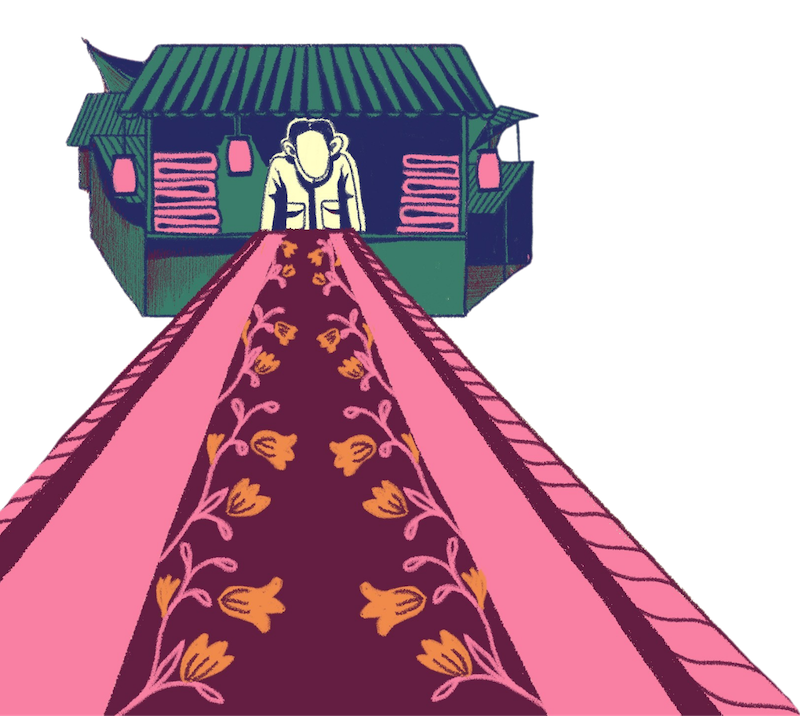

The allure of the fabric draws much from its legacy: Its name translates to “king of wool” (shah translates to king, and toosh means wool). This nomenclature can likely be traced to the 16th century documentation of Mughal emperor Akbar, who loved shahtoosh to the point of almost legislating against its use outside the royal courts. In fact, in his documentation in 1821, East India Company employee William Moorcroft recorded how Akbar allowed only two looms to be used to weave pure shahtoosh. Beyond the luxe factor, the fabric fibre happens to just be 10 microns in diameter. Microns are used to measure small objects or particles, and are equivalent to one millionth of a meter. In comparison, a pashmina is 12 microns, and merino wool is between 18 to 24 microns. This makes the fabric incredibly light. So light is the woven fabric that it’s touted to pass through a wedding ring, and so warm it is believed as capable of helping hatch an egg. By 1975, when the global ban on shahtoosh was imposed, the fabric was being sold by leading brands from Hermes to Yves Saint Laurent. Shahtoosh continues to be flaunted by the global elite: the American lifestyle expert and celebrity entrepreneur, Martha Stewart, flaunted travelling with shahtoosh as recently as in 2017 (she later retracted this claim).

Officials Asian Dispatch spoke with state that the global crackdown on shahtoosh sales has been effective. However, over the years, hundreds of shahtoosh products have been seized, and many have been arrested globally for selling the product. Now, as part of a cross-border project helmed by Asian Dispatch, journalists from India, Nepal, Pakistan, and the UAE have produced exclusive interviews, and new details have emerged to reveal a complex narrative around the shahtoosh. The broader thrust of the narrative indicates that authorities need to revisit the implementation of the ban, and ensure further collaboration to crack down on the illicit black market.

The Kashmir Story

“Chori se chalta hain abhi bhi (It secretly continues even now),” Shabbir Ahmed, a second-generation weaver from Srinagar who used to weave shahtoosh before the ban, tells Asian Dispatch. “If [authorities] find out, [the culprits will] surely get raided.”

Najeeb Mushtaq, a third-generation trader of Kashmiri shawls, whose family transitioned from shahtoosh to pashmina trade after 2000, says, “Every second house in the Old City was a weaver [of shahtoosh]. They were compensated well for their craft.”

Most former shahtoosh weavers Asian Dispatch spoke to attested to the ongoing illicit trade. One trader, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that they still get orders for shahtoosh. This trader refused to say whether they fulfilled those orders.

The story of shahtoosh seems to be rooted in the physical geography of Kashmir: Historically, Kashmir was a part of the silk route connecting Central Asia, China, and the Middle East. It is also important to note that shahtoosh has served as a strong economic pillar in the past for Kashmir’s dwindling artisanal community. India’s official surveys estimate that up until the ban, the shahtoosh production process involved up to 45,405 Kashmiris, including families, with about 14,293 who had direct involvement in its making. Around 85 percent of them lived in the Old City. By 2002, the population of active shahtoosh weavers was reduced to 15,000 workers, with a Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) report projecting that it would continue to decline. There is no recent official survey of the shahtoosh weavers.

According to an estimate by the Wildlife Protection Society of India, the price of raw shahtoosh wool in the 1990s – before Jammu and Kashmir implemented the ban – ranged between ₹34,000 to ₹60,000 per kilo (With the currency conversion being $1=₹35 at the time). Even though the ban on shahtoosh sales was imposed in Jammu and Kashmir in 2000, it took many years for the fabric to completely disappear from shelves. While it may not have the same retail prominence, it has conveniently slid into the shadows of a thriving black market.

“When the ban was enforced, the traders transitioned to legal livelihoods, but the weavers couldn’t,” says Mushtaq, “[The weavers] didn’t get appropriately rehabilitated by the state or their own community. Many of them were shifted to pashmina, but pashmina is half the price of shahtoosh, and artisans aren’t paid as well.”

Illustration: Mia Jose/Asian Dispatch

Mushtaq refers to the unemployment rate (as of December 2024) of Jammu and Kashmir, which stands at 11.8 percent against the national average of 6.4 percent. Official data shows that despite the significant contribution of the handloom sector in the region’s economy, the industry languishes because artisans are dropping out of it.

Mushtaq says that the wave of unemployment and economic restrictions after the shahtoosh ban compelled some traders and weavers to get sucked into illicit activities. “The ban made these shahtoosh artisans not only unemployed but simultaneously took the respect they had in society. Now they’ve been reduced to smugglers,” he says.

Ahmed, the Old City weaver, told Asian Dispatch that even though he left shahtoosh-weaving when the ban came into effect, people selling illegal shahtoosh still ask him to weave it for them. “Someone contacted me just two days back in fact,” he says, during our interview, in April. However, Ahmed refused since he only weaves pashmina now.

Legality aside, there also remains the question of ethics, and when it comes to procurement of shahtoosh wool, the question of its ethicality depends on who tells the story.

Kashmiri traders and artisans say the wool has always been sourced “ethically” from their counterparts in the neighbouring union territory of Ladakh, who further source it from the Tibet Autonomous Region. The Line of Actual Control, which divides India from China-controlled Tibet, is a disputed and heavily militarised boundary. This region is marked by barren, high-altitude terrain with perpetual sub-zero temperatures – conditions befitting the chiru population. This is the region from where, Kashmiris say, Tibetans used to “gather” shahtoosh wool by collecting it from bushes that caught the chirus’ hair – not by hunting the animals. This argument, however, is contested by conservationists.

There are other complications as well. Musadiq Shah, Senior Vice President of Kashmir Pashmina Organisation, tells Asian Dispatch that many of the post-ban arrests have been based on the detection of chiru’s guard hair (the outer layer of hair or fur) in pashmina products. This resulted in a group of pashmina shawl traders, in 2022, initiating a plea at the Delhi High Court after their export pashmina consignments were alleged to have shown presence of shahtoosh guard hair . They demanded better forensic testing in order to minimise “erroneous” confiscations.

“Our pashmina comes from the mountains, and we often don’t know what threads get mixed,” Shah says. Referring to the 2022 plea, Shah says, “Authorities claimed they’re shahtoosh which we have appealed [to rectify] many times to the textile ministry. Now, we have better testing systems in place, but these seizures have resulted in negative coverage of our people. There were times when our shipments were confiscated, and, by the time they came back from the labs, our orders were cancelled. We had to throw them away.”

At the moment, there is no official market value of shahtoosh products. Before the ban, authors Sherry Rehman and Naheed Jafri, in their book The Kashmiri Shawl: From Jamavar to Paisley (2006), estimated that 100 genuine shahtoosh shawls were exported from India every year. Today, the black-market rate of each shahtoosh shawl is estimated to be anything between $10,000 to $20,000. Rehman and Jafri write that: “Asli toos, or real shahtoos [sic] fibre is hardly used in Kashmir anymore, although international fashion and couture houses still quietly place their orders with their Kashmiri manufacturers.”

Illustration: Mia Jose/Asian Dispatch

The Illicit Journey of Shahtoosh

Wildlife Crime Control Bureau officer and one of the lead researchers of the report, Operation Soft Gold, A Pragatheesh doesn’t buy the argument of “erroneous” chiru hair in confiscated material. “You can’t say the chiru hair just appeared in pashmina wool,” he tells Asian Dispatch, “It’s not a contamination.”

Under his supervision, ‘Operation Soft Gold’ analysed 62 confirmed cases of shahtoosh products seized over the course of 11 years, to ascertain the physical properties of the chiru hair. “We identified the guard hair [of each consignment] and we found that the chiru’s guard hair is hollow. Scientifically, it has an insulating effect, which traps the air and keeps the skin warm for those who wear it,” he said. “This is distinguishable only through a microscope.” However, he adds, “As detection [technology] increases, so does the technique of [the culprits] evading the [authorities].”

Operation Soft Gold unveiled an online network that is brazen in its advertisements. Now, a cursory search on Instagram and Facebook can reveal multiple accounts claiming to sell shahtoosh. The operation corroborated these advertisements with the invoicing details of the seized products. They found that traffickers deliberately mis-declare shahtoosh as pashmina, cashmere and wool – all of which are legally and ethically derived from Indian goats. Once exported, the shahtoosh is then sold directly on retail to affluent buyers, mostly in tourist destinations across the world. The 62 consignments in question comprised 343 shawls and 101 stoles. Together, their valuation, based on the receipts, came to $1,925,464.

The Wildlife Trust of India supports agencies such as the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau in intelligence gathering, field validation and collaboration. Between 2001 and 2019, it assisted with the seizure of hundreds of consignments of shahtoosh, leading to arrests. It told Asian Dispatch by email that, over the years, it has observed a shift in the trade's pattern—from open market sales to more covert operations, “often facilitated through digital platforms or concealed in courier shipments through a well-established network.”

between an online seller and a buyer.

Illustration: Mia Jose/Asian Dispatch

Crucially, Pragatheesh charted out three main routes of how shahtoosh enters India, before leaving for foreign shores: The first is from Tibet via Nepal into Delhi, and then to Kashmir to be woven before it’s exported to other countries. The second is through Nepal’s border with the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand, and then to Kashmir. The last is the direct, albeit more challenging, route from Tibet to Ladakh – suspects likely walk this distance overnight due to the heavily guarded border. From Ladakh, he says, it reaches the traders in Kashmir. In the larger scheme of things, Nepal acts as a critical strategic hub in the raw shahtoosh delivery chain; while Kashmir is where the weaving transforms the raw material into premium ‘export ready’ products.

Neighbour’s Complicity

In Nepal, two huge seizures in 2013 trained the spotlight on the country’s role as a vital transit point for smuggling shahtoosh to other countries, especially India. The country lists the Tibetan antelope as a “protected species” under Nepal's National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act, 1973. Anybody caught with it can face up to 10 years in prison, and/or NPR 75,000 ($550) in fine.

Despite these measures, in January 2013, the Central Investigation Bureau of Nepal Police confiscated 46 bags of shahtoosh wool weighing up to 1,181 kg, and worth about NPR 4.5 billion ($32 million). This was in Nepal's Gorkha district, in Thumi village, which is located in the northern belt about 160 km west of Kathmandu. The Gorkha district borders the Tibetan Autonomous Region from the north.

A month later, another 400 kgs of shahtoosh wool was seized from Dhading district, which is also north of the Tibet border. Among the six arrested and charged was one Tibetan national, whom the police say came to Nepal two months prior to the heist to help identify chiru population in Tibet. “It takes around 2-3 days to reach the border that Nepal-China shares from the place where we seized the fur,” Bhola Bhatta, the deputy superintendent of Nepal Police, told Asian Dispatch. Bhatta worked on wildlife cases as an inspector in 2013. “It took me three years to arrest one of the main accused – this shows how complex the network was.” Considering the quantum of the consignments seized, experts Asian Dispatch’s Nepal correspondent spoke to claim that seven to ten thousand Tibetan antelopes may have been killed for that amount of hair.

However, more than a decade on, Sudhir Raj Shahi, the Central Investigation Bureau’s spokesperson and the information superintendent of police, says that there has been no shatoosh seizure since 2013. When asked what explains this period of lull in activities, Shahi said, “Because of our law enforcement, [the smugglers] might have changed the route.”

Whether the smuggling routes to or from Nepal have changed remains a moot point, although Pragatheesh, the researcher at India’s Wildlife Crime Control Bureau, says that the country remains a crucial transit point.

What is more evident, however, is the markets that continue to thrive next door in Pakistan, and beyond South Asian borders too.

Divided By Borders, United by Shahtoosh

At a posh supermarket in Pakistan’s Islamabad city, dozens of women in the premium section of a shawl store asking for shahtoosh shawls is a common sight. The priciest shahtoosh shawl, one store seller says, can cost up to PKR 1.5 million ($5,329). But the hefty price tag is not a deterrent for these wealthy women.

Illustration: Mia Jose/Asian Dispatch

As the store assistants display different varieties of the shawls, the shop owner reveals the range of “shahtoosh”. “It starts at PKR 400,000 ($1,421) and can go up to PKR 1.5 million ($5,329),” a shop owner said. However, adds the owner, a person with “legitimate income” can't afford pure shahtoosh. “Its price in Pakistani rupees is over five million, or even more."

Pakistan has in place a fine of up to PKR 1 million ($3,552) and a jail time of up to two years for trading shahtoosh. Despite that, shahtoosh is publicly adored and offers the elite bragging rights – until it draws online attention, and outrage. In December 2021, Junaid Safdar, the son of Pakistani politician Maryam Nawaz Sharif, wore shahtoosh at his wedding, and instantly came under public scrutiny after the brand behind it claimed that it sells “antique gold original shahtoosh” for $17,000. “When it’s old, the natural colour turns to gold,” their post claimed.

Dr Mumtaz Malik, the former chief conservator of wildlife in Pakistan, says that Pakistan has yet to effectively implement policies related to the chiru. “Despite being illegal, these shawls are still worn by a specific segment of the elite class in Pakistan. Legally, Pakistan is obligated to curb this trade, yet the shawls are available in upscale outlets in major cities like Lahore and Karachi,” says Malik.

Back in Islamabad’s supermarket, the store owner says, “Both shahtoosh and pashmina shawls are smuggled into Pakistan via Gulf countries, especially Dubai, from Kashmir… If immigration officials at the airport create problems, they are bribed. Nowadays, they are often brought to Pakistan in large shipping containers under the guise of import-export businesses." In Pakistan's cultural hub of Lahore, the main town in the province of Punjab, there’s a fabric store in a market area called Liberty, where the price of a shahtoosh shawl starts from PKR 2.8 million ($9,947).

Two traders in Lahore and Islamabad said that dozens of shahtoosh shawls worth millions of rupees were recently gifted to the wedding party – including the bride and groom – of a prominent politician’s daughter. Some of the shahtoosh shawls were worth PKR 2.5 to 5.5 million rupees ($8,881 to $19,540).

There is a general awareness of the shahtoosh ban among the traders. The sale and purchase of shahtoosh, thus, doesn’t take place in ordinary retail shops. In a shawl store in Lahore, for instance, shahtoosh shawls were kept inside locked suitcases in a hidden room behind the main counters. Further, there is no official or unofficial data on the sale of shahtoosh; neither is there any media reporting on the seizures and arrests related to its illicit trade.

The big question around the shahtoosh in Pakistan relates to its authenticity. Malik says that it’s a challenge to identify genuine shahtoosh – even for wildlife officials – in Pakistan because of poor detection technology. “Immigration staff at airports are ill-equipped to identify the material, and in many cases, wildlife personnel are not posted at the airports,” she says.

Jaleel Khan, a trader who repairs used pashmina and shahtoosh shawls in Lahore, says that the average person is prone to becoming a victim of deception due to poor knowledge of shahtoosh. "People who are unfamiliar with [shahtoosh] end up buying pashmina shawls under the label of shahtoosh," Khan said, "Women from elite classes are often deceived in this manner.”

"Real shahtoosh is very costly," said Khan, "The expensive ones come through Kashmir and Dubai. The price for these shawls ranges from PKR 2.5 million ($8,881) to PKR 15 million ($53,291). People openly sell these under the guise of premium products," he said.

UAE: Core Customer Base for Shahtoosh Beyond the Sub-continent

There used to be an assumption that the majority of shahtoosh clientele lay in Europe, Pragatheesh at India’s Wildlife Crime Control Bureau tells Asian Dispatch. But he realised he was wrong soon: A majority of the consignments were headed toward the Middle-East – 18 percent to Oman, and 17 percent to the United Arab Emirates. Other destinations from the region include Riyadh (12 percent), Saudi Arabia (12 percent) and 10 percent to Switzerland. Spain, Mauritius, Italy, China and Hong Kong are other destinations.

Wealth is a big factor for the UAE to be a hub of shahtoosh clients. In 2023, the average per capita net wealth of the UAE was $2.9 million. Last year, it was the world’s top destination for the wealthy, with an inflow of 6,700 millionnaires, according to the Henley Private Wealth Migration Report. This now stands in contrast to the past when the shahtoosh’s primary market was Europe.

Illustration: Mia Jose/Asian Dispatch

After Oman and the UAE, Switzerland – otherwise known for its tight borders and hundreds of seizures – was a close third, with 10 percent of Operation Soft Gold’s contraband headed there.

Over the years, Switzerland has focused on shahtoosh by cracking down on its wealthy buyers in the country. On the contrary, the Indian subcontinent primarily cracks down on smugglers.

In 2017, Swiss authorities raided the Alpine resorts of St Moritz, which unveiled 131 shahtoosh shawls worth up to $20,000 a piece. Lisa Bradbury, from the Swiss CITES Management Authority, agrees that the illicit markets are shifting, but this relies not just on the Middle-East’s wealth factor but also cultural and sentimental factors. “Shahtoosh is in demand among people with a long-standing tradition of wearing shahtoosh, or where you see a lot of family culture of owning luxury items,” she told Asian Dispatch.

Dubai recorded nearly 100 seizures right after the shahtoosh ban in the 2000s. While many of the crackdowns took place in physical spaces such as the Global Village, an analysis by Asian Dispatch found that shahtoosh sales have now moved to the online space in the region.

In one Emirati clothing brand called “Shal”, its owner is seen in several videos talking about selling shahtoosh from Kashmir among other fabrics, mentioning they sell only a limited number of these items. Another website, Alkhazam Gulf Garments, too, claims to sell shahtoosh through their videos on Instagram, although the source of the fabric or the wool isn’t detailed on the website. Their prices start from 148 Emirati dirhams (approximately $41). All transactions are conducted online, but when Asian Dispatch called on their local phone number, there was no answer.

Instagram page, taken on June 18, 2025

Another page called “Shatosh Shall” promoted alleged shahtoosh products on their TikTok channel. Asian Dispatch called Shatosh Shall shop on their listed phone number and a man confirmed they have shahtoosh products from Kashmir. However, he declined to reveal how he obtained them. The shop claims to sell shahtoosh starting from 5,000 Emirati dirhams (approximately $1,500) for a single shawl meant to be worn as a luxury head covering for Emirati citizens. He confirmed that they are all "authentic, handmade," and come with a one-year warranty.

Another Instagram page, with nearly 5,000 followers, called "Tayeb Zabeel," also claims to sell shahtoosh products. When contacted by phone, its shop owner told Asian Dispatch that shahtoosh products are "very rare" but that he still sells them, with prices starting at 10,000 dirhams (approximately $2,700) per shawl. He confirmed that shahtoosh products are "authentic, handmade," and can be used as a head covering for men, which is the traditional Emirati garment, the ghutra. He also noted that he has some shahtoosh shawls for women, at roughly the same prices. To complete the purchase process, orders are placed via WhatsApp, and delivery is available to your home.

While the majority of shops refrained from revealing how they obtained the shahtoosh, many admitted to have “imported” it as handicraft items from Kashmir.

Economic expert Dr Abdul Nabi Abdul Muttalib, who is also the undersecretary at the Egyptian Ministry of Trade and Industry, told Asian Dispatch that the only way shahtoosh enters the UAE is through "smuggling". “This could be through facilitation provided by some influential people inside the country," he says, “whether from governmental or private entities.”

"Sometimes, members of diplomatic missions smuggle these products, taking advantage of the fact that their belongings and bags are not inspected,” he added. Muttalib points to Dubai's Free Zones, which are designated areas that are granted exemptions from duty and taxes, have simplified administrative processes, and duty-free importation of items including raw materials. A 2020 report titled ‘Dubai’s Role in Facilitating Corruption and Global Illicit Financial Flows’, published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, shows how these zones facilitate illicit activities including organised crime. Muttalib says that many goods enter those zones without "real oversight."

Pragatheesh says the online space reveals a sophisticated nexus of traders and smugglers. “These sellers know multiple languages and they’re highly educated,” he says, “Some smugglers update their location on social media based on where they travel across the world. They often have associates in different countries, who run businesses that are legal and registered. Tracking these businesses helped us draw a pattern and trace their shipments for our investigations.”

Why a Rare Product is Suddenly So Easy to Find

While social media plays a significant role in diversifying shahtoosh’s customer base, the explosion of its advertising also casts aspersions on the credibility of the product.

Shah, Ahmed and Mushtaq – from Kashmir – all believe that the shahtoosh circulating in the black market is either fake, or made from leftover shahtoosh wool, or from existing private collections that haven’t been registered.

In India, registering shahtoosh items – which involves declaring shahtoosh possessions to the government through a unique identifier such a stamp or serial number – became mandatory after the ban. While traders couldn’t keep shahtoosh stocks after the ban, private individuals who acquired shahtoosh before the ban could keep it on condition of getting the item registered.

“Borders are tougher now,” Shah says. “I honestly don’t think there’s new shahtoosh being made – nobody has that kind of capacity to carry out this operation in today’s day and age.”

“The stories you hear in the news, of shahtoosh being sold, could be from the leftover stock that traders are selling illegally,” suggests Ahmed. He adds that after the ban, many traders retained the wool. “Shahtoosh doesn’t get bad but one needs to keep it carefully,” he says. “Back then, traders used to spray a specific kind of perfume to prevent it from getting spoilt. I’m sure the same method is being used now.” Asian Dispatch could not independently verify any of these claims, or the information about the aforementioned “perfume” to preserve shahtoosh wool.

The Wildlife Trust of India says that while some of the smuggled products outside of India might be genuine shahtoosh, there’s merit in considering that many traders falsely label similar-looking wool products to exploit the high market value associated with it.

“Laboratory analysis or forensic examination is often required to confirm the authenticity,” it says. “Without such verification, it’s difficult to be certain. There have also been instances of counterfeit goods being passed off as shahtoosh in international markets.” The organisation added that assuming all confiscated material is legacy stock – as the Kashmiri artisans suggested – overlooks the “persistent demand and continued procurement of chiru wool.”

However, the fakes signal a major diversification of shahtoosh trade. “This is a phenomenon where an exclusive item is reserved for high level wealthy people, but the rest of the people want a piece of it too," says Swiss CITES official Lisa Bradbury, hinting at the proliferation of mixed shahtoosh products designed for a new customer base that has aspirations but may not fall in the ultra-high-income category. “We’ve found shawls that have shifted to a mix of cashmere and shahtoosh, with a higher percentage of cashmere. This reflects in the price and the look of the shawl too.” The Wildlife Trust of India noted that in the beginning of the illicit shahtoosh trade, the ratio of wool used to be 80 percent shahtoosh and 20 percent pashmina. Recent seizures, they say, have shown 40 percent shahtoosh and 60 percent pashmina, or 50-50 percent of both wools.

Over the years, shahtoosh detection has seen advancements. From using microchip tags to discourage traders to sell shahtoosh back in the 2000s, to using DNA testing in order to get accurate results today, the technologies have evolved.

Bradbury says that CITES plays a major role in sharing information globally on the technologies needed to detect shahtoosh. While countries like India are launching advanced DNA sequencing options, Bradbury says that at present, shawls are being treated chemically, making it impossible for labs to extract the DNA, thereby rendering them unreliable tools to detect shahtoosh. However, even old-school observation of trends can help detection. “We had this notion that the design on a shahtoosh is necessarily traditional. But with time, we see shahtoosh being designed for a more modern clientele, with leopard prints or Burberry patterns. For now, we’ve shared this information with all the countries to help with more detections,” Bradbury says.

No End in Sight

In an undisclosed location, Asian Dispatch meets a private individual who requested anonymity to talk about shahtoosh. Without divulging too much detail, the individual says that the fabric is an important part of traditional ceremonies, such as weddings and other family events, and that people in their circle often access it through trusted vendors through private chain of communications. “The vendor always says that it’s a dying art, that its weavers are dwindling,” the individual says. “Nobody ever talks about where the wool came from or that the sale and purchase is banned. The exclusivity, and the way the shahtoosh feels, is where the appeal lies for many wealthy buyers.”

The individual adds that they were not aware of the ban until now. “How would I? There’s no taboo around owning a shahtoosh in my circle. I am sure many people own a shahtoosh even today,” they said. “It doesn’t shock anyone.”

When asked whether the knowledge about the ban impacts whether or how they access shahtoosh in the future, they say that they’re just a small part of the problem. “There’s an argument that there’s supply where there’s demand. But if [shahtoosh] didn’t exist, there wouldn’t be any demand. It’s the supply that creates the demand, you see.”

Meanwhile, on the supply side, in Kashmir, there have been localised efforts by some traders who are advocating for the decriminalisation of shahtoosh. In 2018, the Ministry of Environment and Forests rejected a suggestion to do captive breeding in order to bring back shahtoosh weaving.

Photo: Weichao Deng via Unsplash

Musadiq Shah, of the Kashmir Pashmina Organisation, recommends a global and collaborative pilot project to regularise shahtoosh shearing under controlled conditions. “There should be a scientific way to bring back shahtoosh. We are against killings. But we would want to give a chance to rehabilitate the weavers,” he says.

In the wildlife community, there’s a unanimous consensus that this is not feasible. “It’s not possible to keep the Tibetan antelope in captivity and shear,” says Swiss official Lisa Bradbury, “This animal is not meant to be in contact with humans. The idea of ethical shearing of chiru wool is not possible.”

Back in Kashmir, Mushtaq says that there should be more scrutiny on those who seek illicit shahtoosh rather than the middlemen who supply it, many of whom just happen to be desperate locals in need of employment.

“I, as an honest trader, sell pure pashmina. But I get paid far less than someone who passes off their dodgy product as shahtoosh,” he says, “This deceitful trade is hurting all of us.”

CREDITS

LEAD REPORTERS

Pallavi Pundir, India

Hashim Hakeem, India

Rajneesh Bhandari, Nepal

Sajjad Tarakzai, Pakistan

Wael Elghoul, United Arab Emirates

PROJECT MANAGER

Preeksha Malhotra

STORY PRODUCTION

Anoushka Dalmia

VISUALS

Mia Jose

Shashank Raj

Sharanya Eshwar

EDITOR

Asad Ali

SPECIAL THANKS

Mike Shanahan, project director, Biodiversity Media Initiative (Earth Journalism Network)

Dr Mark Lee Hunter, veteran journalist, author and media educator

This multimedia investigation was produced by Asian Dispatch with the support of the Earth Journalism Network and originally published here.

DISCLAIMER: No money or gift has been exchanged or transactions agreed upon during any part of this reporting in any country.